“Carceral feminist” is the phrase Valena Beety used to describe her old self, when she was a law student and prosecutor. The author of the forthcoming criminal justice book Manifesting Justice believed in the power of locking people up to “stop cycles of violence,” as many perpetrators of violent offenses are repeat offenders. “There’s a place for incarceration for people who have been dramatically violent.” She believed in her victim advocate work.

As a trial prosecutor, she grew weary of prosecuting defendants who tended to be poor Black and Brown men. And she came to realize that prosecution didn’t necessarily keep violent offenders away from people who they could hurt. “They’re usually back out quickly, and there’s nothing to help them resolve their violent behavior in prison.”

And she learned lessons that charted a new career path for her: Police aren’t always honest. The system isn’t always fair. Innocent people can wrongly confess.

Innocent people can be wrongly convicted.

“I didn’t think of that possibility before,” she said, pointing to the discretion prosecutors are supposed to exercise to avoid convicting the innocent, and their mission of pursuing justice rather than tallying convictions. “But once that window opened, I couldn’t look away.”

A book on disproving guilt

Her book, Manifesting Justicetakes an unflinching look at the lessons she learned on her journey from prosecutor to innocence attorney to criminal justice policy advocate.

The central story, the wrongful prosecution, conviction, and imprisonment of two lesbian women, Leigh Stubbs and Tami Vance, led to Beety’s first exonerations. They had served more than a decade in prison for a crime they did not commit when they were released.

Some cases for which she advocated freedom for incarcerated people are still being litigated, and many could have served as the central story of her book. One involves the four foot, nine inch Tasha Shelby who Beety says was wrongfully convicted because, as Beety puts it, “prosecutors’ believe in the rightness of what they’re doing and put on blinders.”

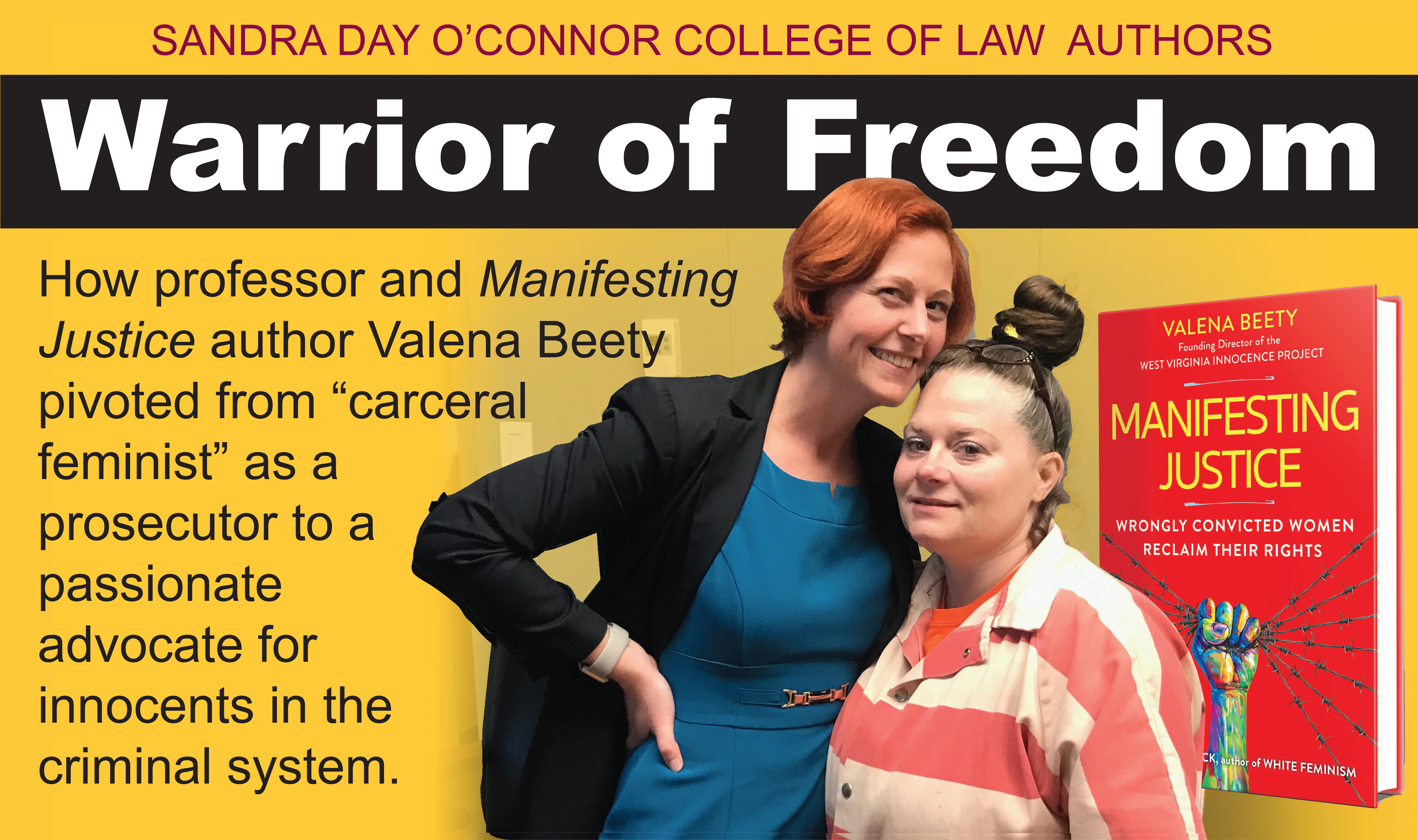

Tasha Shelby, pictured above with author Beety, was convicted on a scientifically problematic theory of shaken baby syndrome when the child was two and a half years old, thirty pounds, and three feet tall. Two weeks before the death of the child more than half Shelby’s height, Shelby had surgery and stitches in her body that would have precluded her from lifting anything heavy, let alone killing the child.

The case, which is addressed in Manifesting Justice, is currently back in court and has been ongoing since 2011.

How to prove innocence

Beety says that the process of proving innocence can be difficult, but is rewarding. She points to her previous work, The Wrongful Convictions Reader, as a guidepost for learning the process of innocence work, which involves looking beyond the trial record, finding evidence to be tested, analyzing how the case went wrong, and writing long, persuasive pleadings.

But there are hurdles. Prosecutors oppose postconviction DNA testing. Courts are reluctant to reopen cases that have been finalized. Usually, it requires newly discovered evidence, as in the case of Leigh and Tami, an FBI report casting doubt on key video evidence used to convict.

And courts are very reluctant to dislodge evidence. Eddie Lee Howard was wrongfully convicted in 2004 based on the testimony of scientific expert Dr. Michael West, who had been proven to have testified incorrectly in other cases. The Mississippi Supreme Court, however, found that just because West had been wrong in other cases didn’t mean he was wrong in the case being considered. The innocent convict had to wait years longer, until 2021, to be freed.

As for Leigh and Tami’s case, “We had to have a lot of evidence”: an FBI report, bite mark experts to counter Dr. West, and an affidavit on LGBTQ bias. Bite marks in particular have been widely discredited in scientific literature, but Beety notes that courts are still happy to admit them as evidence.

The FBI report led Beety to take on Leigh and Tami’s case. In 2009 she was the attorney who took the lead investigating and litigating it. Beety chose this case as the focal point of her book to highlight a gap in the literature of wrongful convictions, which rarely features women, let alone women in the LGBTQ+ community.

The author’s life today

Prior to writing Manifesting Justice, Beety produced scholarship and popular works on topics including victim compensation, forensic science, eyewitness testimony, drug enforcement and the overdose epidemic, and LGBTQ+ studies. She has no plans to slow down, planning to produce a book from a research project involving interviews with dozens of women in all aspects of innocence work, including wrongfully convicted women.

Now a professor of criminal law at Arizona State University, she has worked with students and graduates to produce a manual on wrongful convictions and manifest injustice claims. A big point of the book is that the factual innocence standard must change to manifest injustice or miscarriage of justice—potential biases should be examined in conjunction with a confluence of errors such as discredited evidence or faulty confessions.

She also keeps in touch with clients. “When they walk free, the bond doesn’t end.” She notes that innocence attorneys often stand in as social workers for innocence clients. She notes that the wrongfully convicted are imprisoned for an average of ten years before being freed, and many have ongoing convictions that remain on their records until finally expunged.

Beety has always relocated for her work, having migrated to Mississippi to litigate death penalty cases and moved to West Virginia to found an organization on proving innocence claims. Now, she lives in the Phoenix area while working at ASU with her wife, her Boston Terrier, Eva, and her cat, Moonshine. She loves the urban and rural mix of Arizona and its great hiking, and hopes it be home for a long time to come.